Sprint races can be decided by hundredths of a second. But the sprinter who pushes off before the starting gun sounds “jumps the gun” and faces harsh punishment. In our never-ending attempts to make competition law sound cool, practitioners refer to the completion of a deal before mandatory clearance is obtained as “gun jumping”, even though participants in this race have plenty of time to anticipate the starting gun and react accordingly.

While the analogies with sports are clearly limited, they do hold when it comes to the draconian nature of the penalties imposed for gun jumping. Athletes often face disqualification. Today, the European Commission announced it imposed a record penalty of EUR 432 million on Illumina for closing its acquisition of GRAIL prematurely. This is the highest ever fine for “gun jumping”, the previous record was EUR 125 million, imposed on telecom company Altice. The fine is even larger in relative terms, amounting to about 10% of Illumina’s worldwide turnover, compared to only 1% in the case of Altice.

10% of global turnover is the maximum penalty the European Commission can impose. Why did it go as high as this? Let’s first recap on the background, and then dive into this question, after which we will discuss some broader themes.

Background

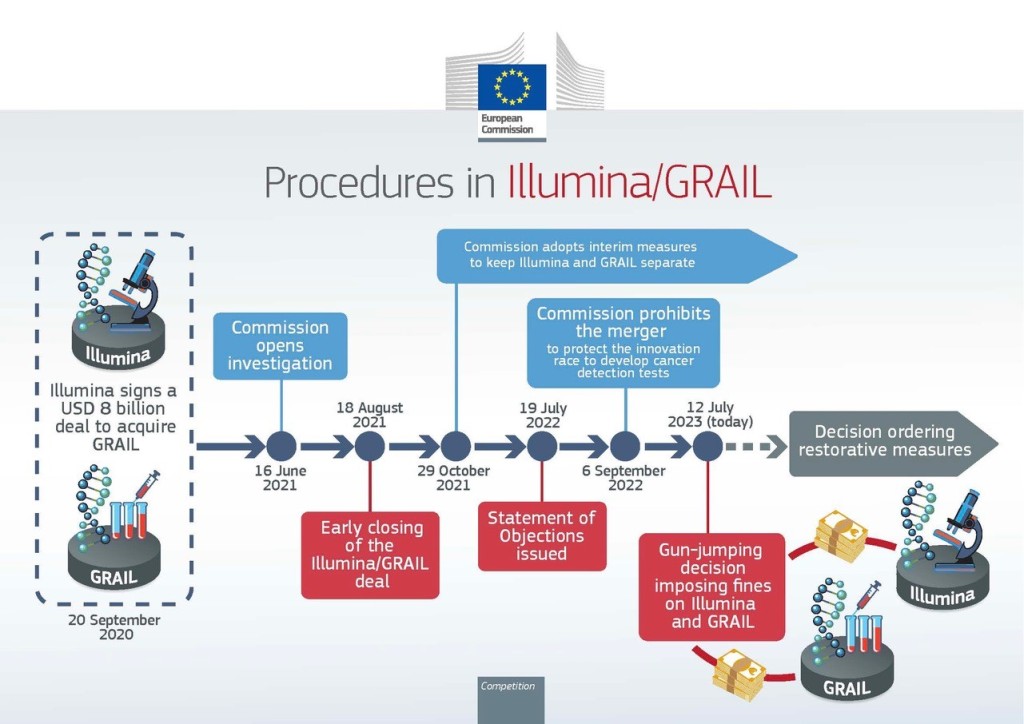

As we have explained in previous posts, this case is somewhat unusual, because the deal fell below the mandatory notification thresholds in the EU. It was also not mandatory to file it within any individual EU Member State. Nonetheless, France, supported by a number of other Member States, referred the deal to the European Commission for a review under Article 22 of the EU Merger Regulation (EUMR). The general consensus among EU lawyers at the time was that Article 22 could only be used for a referral to the Commission if the transaction was notifiable under the rules of one or more Member States. In other words, the commonly held view was that Article 22 could not be used to refer a merger to the Commission that did not require notification in any EU Member State.

That assumption turned out to be wrong. The Commission accepted France’s referral, which Illumina challenged at the EU’s General Court and lost. Pending that appeal, the Commission had opened an investigation into the deal, referred it to an in-depth inquiry, and ultimately blocked it. The opening of a merger investigation by the Commission means that a standstill period applies during which a deal cannot be completed except in exceptional circumstances. This is no different if the inquiry is opened after an Article 22 referral, except if the deal was already completed before the referral was accepted (which was not the case here).

The commencement of this standstill period put Illumina in a catch-22 situation (pardon the pun), since it had agreed to pay a break fee to GRAIL’s owners of USD 300 million if the deal was not completed by end of August 2021. There was no “condition precedent” of Commission clearance in the SPA, because Illumina had assumed that such clearance was not required. Thus, Illumina faced a choice between breaching the standstill period but escaping the break fee or respecting the standstill period but having to pay the break fee. It opted for the former, and closed the deal in August 2021, right in the middle of the Commission’s inquiry. The Commission opened a gun jumping inquiry just two days later and took the unprecedented step of imposing interim measures to restore and maintain competition by ordering Illumina to hold GRAIL separate from Illumina’s business. Illumina, meanwhile, challenged the Commission’s opening of proceedings in the General Court, which it lost. It then appealed the General Court’s decision to the Court of Justice in a case that is still pending (GRAIL has also appealed). Illumina also appealed the Commission’s interim measures decision as well as the Commission’s decision blocking the deal. These two challenges are still pending.

The fine – And why the Commission had little choice but to push the boundaries

Having blocked the deal and being 1-0 ahead in the courts, the remaining outstanding question at Commission level was what the outcome of its gun jumping inquiry would be. Back in January, it was reported by Reuters that Illumina had set aside $453 million for a potential EU fine, suggesting that it was preparing for the worst. That precaution was not unwarranted, as the Commission imposed a penalty of EUR 432 million on Illumina today.

Illumina’s worldwide turnover in 2022 amounted to USD 4.53 billion, meaning the maximum fine the Commission could impose was USD 453 million, i.e., 10% of worldwide turnover. Arguably, Illumina gave the Commission little choice but to go as high as that.

The Commission is clearly of the view that Illumina’s breach of the standstill obligation was committed “knowingly and intentionally” and that it constitutes “an unprecedented and very serious infringement”. In the Commission’s opinion, such an infringement requires “the imposition of a proportionate fine, with the aim of deterring such conduct”.

Although the Commission doesn’t mention it in its press release, the reason for such a high penalty can also be linked to the break fee that Illumina was required to pay to GRAIL’s owners if it did not close the deal by end of August 2021. That break fee was set at USD 300 million, and Illumina was at pains to point out that it would be losing that amount if it did not close the deal on time. The suggestion was that it was between a rock and a hard place, and had no choice but to breach the Commission’s standstill period to avoid having to pay the break fee.

However, such self-inflicted damage seldom wins over the regulator. To understand why, it is important to take the regulator’s point of view of the situation, which is based on the concepts of general and specific deterrence. The goal when setting the level of a financial penalty is, at least in theory, to set it at a level that would deter the company involved (here, Illumina) and others from repeating the same mistake. It’s not too dissimilar to the position in sports. If a false start is not harshly penalised, athletes are incentivised to try and beat the starting gun, even by a few hundredths of a second, which would then be highly disruptive if it led to many re-starts without disqualification of the athletes concerned.

To achieve both general and specific deterrence, it is settled case law, at least in the context of cartels, that a fine pursues not only a preventative, but also a punitive objective, and that a fine cannot be set at a level that merely negates the profits of the cartel (see, e.g., Case T-59/02 Archer Daniels Midland v Commission). The idea is that when managers make decisions, they take account rationally not only of the level of fines that they risk incurring in the event of an infringement but also the likelihood of the cartel being detected. Since the likelihood of detection is never 100% (in fact, it is often far lower than that), it would be rational to opt to break the law if the penalty was equal to the profits from the infringement.

In short, to deter companies from breaking the law, it cannot be the case that crime pays. Applying this to gun jumping: if it was cheaper to jump the gun than to pay the break fee, gun jumping would become normalised in situations like the present one, and managers would be seen as “rational” in ignoring the standstill period. This is because respecting the standstill period carries a cost (the break fee of USD 300m) which is avoided in the scenario where the standstill period is not respected. To make that scenario the least attractive for the company involved but also for other companies who will be looking at the actions the Commission takes in this case, the Commission had to make the scenario of non-compliance even more costly for Illumina than the scenario of compliance. The fine had to be larger than the break fee by some margin, provided this did not breach the 10% cap.

Having set this precedent, the Commission has sent out a strong message that the standstill obligation applies without reservation if a deal is referred to it under Article 22. As a result, it has with one single case made clear how seriously dealmakers should take this provision.

The significant evolution in EU merger control

The Illumina case is not only relevant because of the record fine imposed by the Commission. Its broader relevance lies in its role as one of a potential trio of cases which has brought about a quiet revolution in EU merger control rules: Illumina/Grail, Towercast and Three/O2. Each of these cases is important, but the whole may be stronger than the sum of its parts, especially together with the requirement in the Digital Markets Act (DMA) that the big tech firms who will be designated as “gatekeepers” under that legislation will need to notify the Commission of any intended acquisition irrespective of whether the deal meets the EUMR’s notification thresholds (DMA, Article 14).

When the Commission’s block of the Three/O2 merger was overturned by the General Court in 2020, many wrote off the EU as a jurisdiction where novel theories of harm could be used to scrutinise deals. The common view was that the EU had high notification thresholds, and for mergers that met those thresholds, the General Court had set a high standard of proof for the Commission to meet, particularly in so-called “gap cases”, i.e., cases that do not involve the creation or strengthening of a dominant position.

Little did we know that three years later, the EU jurisdiction looks more muscular than ever:

- The Illumina/GRAIL case has demonstrated how the Commission can “call in” mergers that fall well below the EUMR’s and national notification thresholds, giving the Commission an option to call in “killer acquisitions” where an incumbent is buying a potential competitor (as also outlined in the guidance it published after the French referral). Also, as discussed below, it shows a willingness on the part of the Commission to consider vertical theories of harm relating to potential competition;

- The Towercast judgment allows the Commission and national competition authorities to scrutinise completed mergers that were not reviewed under the merger control rules as a potential abuse of a dominant position under Article 102 TFEU (and the Belgian competition authority has already launched proceedings into the acquisition by Proximus of edpnet on this basis);

- The DMA will mean that the Commission will be notified of any acquisitions by gatekeepers, thus giving it the possibility to use Article 22 EUMR to “call in” such deals where appropriate; and

- The Commission will be hoping that it wins its appeal against the General Court’s judgment in Three/O2 after it already obtained a positive Opinion from Advocate General Kokott. If it does, the Commission will not have to deal with the heightened standard of proof that the General Court considered applies in merger cases. The judgment will be out on 13 July.

Together, these cases mean that the EU’s merger control regime may suddenly look stronger than ever. While the UK’s Competition and Markets Authority has been grabbing the headlines with its tough position on tech mergers like Facebook/Giphy and Microsoft/Activision, the EU has quietly achieved some major results in the Courts and in legislation. It will effectively be able to call in below-threshold mergers, it will be made aware of such transactions if they are contemplated by gatekeepers under the DMA, insofar as it has missed a deal, it has scope to review it under Article 102 TFEU, and it is showing already that it is willing to consider dynamic theories of harm (and it will hope to be bolstered by a positive judgment in Three/O2).

From the point of view of competition practitioners and companies looking to do deals, the Illumina/GRAIL saga may be just as consequential as Microsoft/Activision: not only did the Commission call this deal in on the basis of a novel interpretation of Article 22 EUMR, it then proceeded to block it outright, like the CMA blocked Microsoft/Activision (still under appeal).

A marathon, not a sprint

Indeed, all the focus on the procedural issues in Illumina/GRAIL may well detract from the substance of the case. Although the Commission’s blocking decision has not yet been published, it is clear from the press release that the Commission’s concerns relate to GRAIL’s blood-based cancer detection test, which is still in development. Sticking to the theme of this blog post, the Commission held that GRAIL is “in a race with other companies” to be the first to successfully develop and market such tests.

Illumina is not part of that race as it does not compete with GRAIL. It is, however, currently the only credible supplier of a technology able to develop and process these tests. The Commission is concerned that “Illumina would have an incentive to cut off GRAIL’s rivals from accessing its technology, or otherwise disadvantage them”. Thus, it is worried that GRAIL’s future rivals will be foreclosed from the market, which would allow GRAIL to monopolise it.

While the detailed decision must be read to properly understand the Commission’s position, it is very interesting to see the Commission taking the step of blocking the acquisition of a company with no sales in the EU, on the basis of the impact of putative foreclosure on potential competition, in circumstances where nobody has yet successfully launched a blood-based cancer detection test.

This is perhaps not as speculative as the CMA’s finding that Activision will launch its games on cloud gaming services when it had publicly stated it would not be doing so, but it sure is a dynamic theory of harm. Also, the real-life impact of the Commission’s decision in Illumina/GRAIL is potentially much more significant than the CMA’s block of the Activision deal. In a race to become the first to launch a potentially life-changing technology, any distraction can cause delays. Management at Illumina and GRAIL have been dealing with regulatory issues for almost three years (including also multiple appeals in the US).

There are still big prizes to be won by Illumina in the courts. If its appeal against the General Court’s judgment relating to the interpretation of Article 22 is successful, this would invalidate the Commission’s case in its entirety. If its substantive appeal against the Commission’s blocking of the deal succeeds, today’s gun jumping fine would probably not be affected, but at least it would finally clear the way to bring home a deal announced in September 2020, at least so far as the EU is concerned. Finally, if it loses the two existing appeals but successfully appeals today’s fine, it may be able at least to reduce its financial exposure in this case. However, overturning the European Commission in cases like these is difficult in practice.

Whatever the outcome, it is clear that instead of a quick sprint, Illumina and GRAIL find themselves in a regulatory marathon. Only time will tell if we will ultimately have a more competitive market for blood-based cancer detection tests or if this case ends up delaying the introduction of those tests. The stakes are high.

Stijn Huijts is a partner at Geradin Partners. Photo (c) Reuters. Image (c) European Commission.

One thought on “Draconian but unavoidable? Illumina’s quest for GRAIL ends in a record fine”